Heat Stress

Heat stress in cows

Cows take on heat from the environment and generate metabolic heat from eating and digesting feed. Problems start to occur if temperature and humidity increase and cows don't have opportunities to balance their metabolic and environmental heat gains.

What causes cows to get hot?

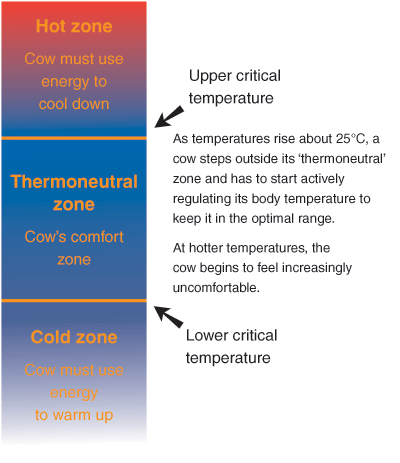

Like most mammals, the dairy cow needs to maintain its core body temperature between 38.6ºC and 39.3ºC. The core temperature changes slightly throughout the day, reaching a peak in the early evening and a low early morning.

Metabolic heat is being produced all the time. During the day this heat is not as easily dispersed. If night time conditions are sufficient to allow adequate dispersal of heat the cow will not suffer ill effects. If this diurnal cycle of heat accumulation during the day and loss during the night is disrupted by high night time temperatures the effects become more noticeable.

Factors that determine the level of environmental heat a cow is exposed to over time are:

-

air temperature and relative humidity

-

amount of solar radiation

-

degree of night cooling that occurs

-

ventilation and air flow

-

length of the hot conditions.

Register to receive alerts sent directly to your phone via heat alert service.

How do cows keep themselves cool?

In hot environmental conditions, cows off-load heat with a range of behavioural and physiological strategies.

Dairy cattle may change their behaviours by:

-

looking for areas with greater air movement or standing to increase or exposure to air

-

seeking water and shade

-

changing their orientation to the sun

-

panting or sweating, or

-

stopping or reducing feed intake which decreases rumen heat production.

As heat load builds the cow's body struggles to cope.

Excessive heat load

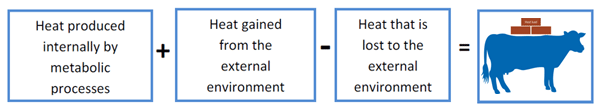

A dairy cow manages the body heat load that it carries within itself all the time. If the sum of metabolic heat produced by the cow and the heat gained from the external environment begins to exceed that lost, the cow's heat load starts to build.

The cow must ensure it stays within the optimal range through thermo-regulation. This means balancing the metabolic and the absorbed environmental heat using a a range of strategies, such as increased breathing rate and sweating.

It is important for dairy farmers to know the signs of excessive heat load so practical strategies can be implemented to help the cows cope.

Once heat load reaches a critical point changes start to occur in metabolism, hormonal regulation and feed intake. This in turn affects milk production, milk quality, fertility and health.

Managing heat stress in cows

Awareness of the signs will inform your decision-making around the management and response to heat stressed cows.

Looking for subtle changes in behaviour will give you plenty of time to act. If the period of excessive heat load lasts more than a few hours signs of heat stress become more marked.

Open mouth breathing, group seeking of shade and excessive drooling are all signs of prolonged heat stress and call for urgent attention.

Recognise the early signs of excessive heat load and allow for early intervention with effective management and mitigation strategies, such as access to shade and cooling infrastructure, water access and feed pad usage.

Physiological responses to excessive heat load

Apart from observable changes in behaviour, there are also a number of unseen physiological changes that occur within cows, such as:

-

feed intake decreases by 10-20% when the air temperature is more than 26°C

-

core body temperature rises

-

blood hormone concentrations are changed

-

blood flow distribution is altered, blood flow to gut, uterus and other internal organs is decreased, blood flow to skin is increased.

The unseen changes can have far-reaching consequences on the productivity, health and welfare of cows.

Shade and cooling

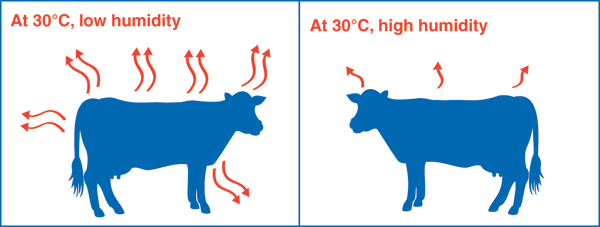

Increasing air temperature and humidity reduce the cow's ability to cool itself.

Shade is the most important consideration for reduction of heat stress.

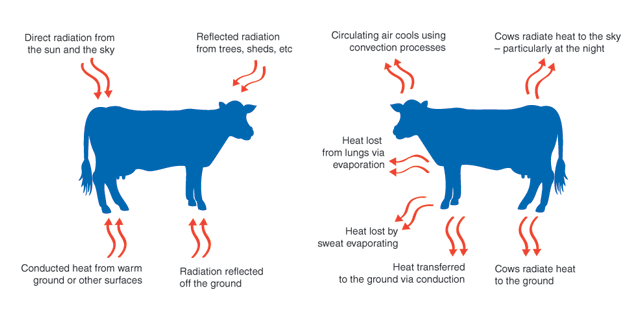

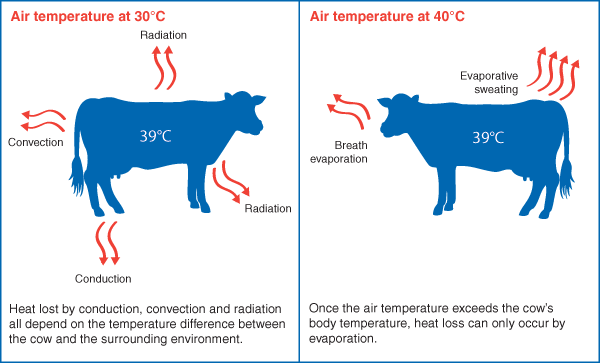

Heat exchange between the cow and the environment occurs through radiation, conduction, convection and evaporation processes.

The direction of heat exchange depends on the temperature difference between the cow and the surrounding environment.

When the air temperature is higher than the cow's temperature, heat flows into the cow - heat is absorbed. When the air temperature is lower than the cow's temperature, heat flows from the cow - the cow off-loads heat and cools down.

The greater the temperature difference, the faster the flow of heat.

Shade and Cooling

The use of shade is the most important consideration for reduction of heat stress and cooling cows.

Infrastructure to reduce heat stress in cows

Consider opportunities for reducing temperature and evaporation opportunities, via shade and shelter (natural or man-made).

It is worth considering how these can be integrated into existing infrastructure. The main options for shade infrastructure are explained in the Infrastructure pages. These balance the factors that should be considered when investing in cooling infrastructure. The right combination of cooling methods based on how the farm operates is the key to reducing heat stress.

The effect of heat stress on productivity

Heat loads can build when farm infrastructure doesn't provide cooler conditions for the whole herd. Decreased milk production is the clearest cost, but some effects are less obvious and result in significant productivity losses. These include:

- reduction in fertility and calving rates

- low milk components

- body condition loss

- susceptibility to infection

-

Fertility and calving rates

Cows are more likely to have silent heats or shortened heats in hotter seasons. This is a result of reduced activity due to heat as well as alterations in hormonal activity that reduces the expression of oestrus behaviour.

Heat stress has been shown to decrease oestradiol production, a major female sex hormone that regulates oestrous, leading to ovarian inactivity. Alongside this, the hormonal imbalances impair the oocyte development. This results in lower conception rates.

Heat stress will effect the endometrium in the uterus. This can result in reduced ability to sustain a pregnancy and increased embryo mortality. Additionally, growth hormones essential to embryo development are affected by heat stress.

A heat stressed dairy herd may experience a decreased 6-week and 100 day in-calf rates or increased not-in-calf rates. Higher heat loads affect digestion and nutrient acquisition by lowering feed consumption rates, which in turn, can affect the calf birth weight and viability. Reduced access to nutrients essential to calf development will have a negative impact on calf weight and viability.

The risks to calving and fertility presented by heat stress include:

- reduced intensity and length of oestrus

- decreased conception rates

- increased risk of embryo death

- decreased 6-week/100 day in-calf rates or increased not-in-calf rates

- decreased calf birth weight and viability reduces.

-

Effects on milk production and quality

The metabolic changes associated with dissipating heat loads is energy intensive and believed to be responsible for reduced lactation and milk production1. Milk from heat stressed cows can have altered milk components with variations in proteins and fat content2.

A direct effect on milk quality will be due to the reduction in efficiency of the immune system resulting in increased risk of mastitis.

Care should also be taken when implementing any cooling processes with sprinklers. Wet udders when sitting in potentially contaminated areas and immediately prior to milking can result in increased contamination.

Some of the risks to milk production presented by heat stress include:

- milk production can drop by 10-25% during heat stress, 40% in extremes

- milk composition is affected with high to severe heat stress, with a decline in total protein

- increased risk of udder infection, which, if occurs, results in increased somatic cell counts and sediments in milk.

-

Planning and management

Whether you want to make small or big changes, these Top 10 short-term and long-term changes to farm infrastructure provides options for heat stress management.

Ten short term actions to consider

- Set up a sprinkler system at the dairy yard.

- Install a large water trough on the exit side of the dairy.

- On hot days, wet the dairy yard for an hour before cows arrive.

- Delay afternoon milking until 5 pm during the hot season.

- Sprinkle cows for 30 to 60 minutes while standing in the dairy yard waiting for afternoon milking on hot days or when cows breathing rate exceeds 60 breaths per minute or the temperature heat index (THI) is above 78.

- In hot weather, provide cows with the highest quality pasture available to graze overnight when they are cooler.

- Increase your cows grain / concentrate feeding rate, feed high-quality forage fibre and higher-quality protein sources, and increase cows intakes of potassium, sodium and magnesium.

- In very hot days, if you don't have a shade shed, bring the milking herd back to the dairy yard around midday and use the sprinkler system to cool cows - if possible give them access to high quality hay or silage.

- Mate more heifers to compensate for lower in-calf rates expected in milkers during the hot season to help maintain your desired calving pattern.

- Implement a tree planting program starting with trees on the western side of the yard.

Ten long term actions to consider

- Review the whole farm for shade.

- Develop a farm plan that incorporates significant tree plantings over time on the northern and western edges of pastures. Plant deciduous trees along laneways.

- Fence off tree lines to protect tree roots from cow treading and reduce chances of cows lying down in mud and dung.

- Install a shade cloth over the dairy yard to further enhance cow cooling prior to milking.

- Install water troughs in all paddocks and along laneways.

- Combine shade and sprinklers at the dairy yard with a feed out system for high quality forage / partial mixed ration close by. Ensure cows can move freely between both areas during hot weather.

- Build a shade shed with a solid roof set over a feed pad integrated with a PMR feeding system.

- Install a sprinkler system set with temperature controls in the shade shed over the feed pad which is integrated with the effluent management system.

- Install fans if air movement through the shade shed is inadequate.

- Assess the impact of withholding insemination during hot weather on herd profitability.

-

Heat stroke

What to look for

- Rapid breathing (more than 80 breaths per minute) with mouth open

- Restlessness and followed by becoming dull, stumbling and going down

- In terminal stages cows may seizure and die.

Cause

Heat stroke is severe heat stress caused by exposure to a combination of high air temperatures, solar radiation, high humidity and low air flow often for a prolonged period.

Animals likely to be affected

Older, high producing Holstein-Friesian cattle tend to me more susceptible to heat stroke than younger, lower producing cows and Jersey or Brown Swiss breeds.

Confirming the diagnosis

Heat stroke can be diagnosed by exposure to the causes above in combination with a rectal temperature above 42oC.

Treatment

Cows affected by heat stroke should be protected with shade and offered cool drinking water. Cooling by pouring water over the body must be accompanied by increased air circulation such as positioning in front of a powerful fan. Water applied to the body, without air circulation, can exacerbate humidity. Severely affected cows will require treatment with special IV fluid therapy.

Risk factors

- High air temperature, solar radiation, high humidity or low air flow often for a prolonged period

- High producing cows and Holstein-Friesians

- Larger and/or older cows

- Black coat colour

- Cows required to walk further or on hilly terrain

- Cows not preconditioned to hot weather.

-

Heat transfer and cow behaviour

Off-loading heat

Understanding the heat exchange process can support your decision making around providing shade, water and cooling systems to keep cows cool.

Heat Transfer Process

Behaviours

Conduction - the transfer of heat through physical contact

Stand up to increase air flow around its body.

Standing in cool drinking water to lose heat through the hooves.Convection - produces cooling if there's high temperature difference

Stand where there is a breeze or under fans.

Cooling is more effective with higher air speedRadiation - emission of heat to and from the cow and surroundings, directly from the sun or from re-radiation from hot ground, fences, buildings etc.

Cows position themselves away from the sun if there is no shade.

Shading from direct sunlight reduces the solar radiation it receives by 50%

Black coated cows absorb more solar radiation.

However, black coated cows will re-radiate heat more effectively at night.

Heat loss by conduction, convection and radiation all depend on a temperature difference between the cow and the surrounding environment. The greater the temperature difference, the faster the flow of heat. As the air temperature rises this form of heat loss declines.

-

Evaporation

This is the most efficient and primary mechanism cows will use to rid themselves of heat loads. Anything you can do to assist the cows evaporative cooling processes is worthwhile.

Heat Transfer Process

Cooling benefits

Evaporation - heat loss through sweating and breathing

70% of total evaporative heat loss is due to sweating.

30% of total evaporative heat loss is from breathing moisture losses

from the respiratory system.

Small evaporative heat losses also occur through loss of water vapour

from skin independent of the action of sweat glands, and through salivation.Evaporation from the cow surface through sweating will increase with air movement. However, evaporation depends on a difference in relative humidity between the cow skin and the air.

For example, at 30ºC you may be able to achieve good evaporative heat loss in low humidity conditions. If the temperature remains at 30ºC but the humidity level increases, then the rate of evaporative heat loss will decline - keep this in mind when making cooling choices for your cows.

Once the air temperature exceeds the cows' body temperature, heat loss can only occur by evaporation.

-

Mating and heat stress

Increased heat loads during periods of continuously hot humid weather can be severe on conception rates and in-calf rates particularly in higher-producing cows.

Access the InCalf herd assessment tools and the InCalf Book for more information.Mating management

When considering the timing of your calving pattern, it is worth factoring in that mating during hot summer months will have an adverse effect on fertility outcomes.

When considering calving strategies, allow for the following impacts in hot season mating periods.

-

Oocyte quality will be reduced resulting in lower conception rates.

-

This will be less of an issue in heifers than in older cows.

-

Cows are less likely to express oestrus behaviour in hot weather. Heat detection techniques will need to be intensified.

-

Bulls will be less inclined to be active. Increasing the number of bulls might be necessary.

During hot conditions, reduced fertility can be avoided by:

-

minimising the time cows are standing around in hot yards waiting to be inseminated

-

providing a shaded area for these cows

-

increasing the use of heat detection aids.

Heat detection

Cows are more likely to have silent heats or shortened heats in the hot season. Accurate heat detection is critical to achieving high submission rates. Expect cows calved in summer to take longer to start cycling than cows calved in winter.

The key is to increase your heat detection efforts over the summer months and manage cows not detected on heat.

Artificial insemination practices for heat stressed cows

Increased heat loads during periods of continuously hot, humid weather can be severe on conception rates particularly in higher producing cows. It would be prudent to lower fertility expectations for mating carried out during hot periods.

Make sure you are not blaming the hot weather for problems caused by poor procedures. Ensure that all AI practices are up to scratch including general preparation and cow handling, semen storage and handling, insemination techniques and timing.

Calving pattern decisions

Altering calving patterns to avoid extreme heat will only partially address the effects of heat stress on mating performance, conception or calving rates.

The extra cost of cooling infrastructure may deliver better outcomes in herd fertility performance than delaying or changing calving patterns. Extreme heat events should be a just one of the many factors considered when deciding the best management approach.

Calf Rearing

Tips to help dairy farmers rear calves well, manage welfare and manage health, disease and injury as well as other management measures to put in place for ensuring calf welfare.

InCalf book for dairy farmers: 2nd edition

The InCalf book assists farmers and advisors to develop an effective, profitable strategy to achieve farm targets for herd reproduction. -

Nutrition and heat stress

Increases in environmental temperature will suppress a cow's appetite. A noticeable difference in cows experiencing heat stress is a reduction in dry matter intake. Dry matter intake drops by 10-20% short term or long term depending on the length and duration of heat stress. The effort involved with keeping cool can result in 20-30% more maintenance energy needed to compensate.

If in doubt, consult your nutrition adviser.

-

Fats and proteins for heat stress

Higher producing cows and those under greater metabolic stress respond well to this nutritional strategy.

Supplementary fat sources like vegetable oil and commercial ‘by-pass fat’ supplements are regularly used, while proteins provide a good source of amino acids.

How much fat during winter months?

Feeding fat has an added advantage in hot conditions - it is digested and used by the cow more efficiently than starches and fibre and produces less metabolic heat.

Too much fat interferes with microbial digestion in the rumen and depresses feed intake.

Aim for a maximum of 6-7% total fat in the diet (DM basis). Dietary supplementation with extra fat is a good way to help increase the energy density of the cow’s diet and maintain the daily energy intake.

Higher producing cows and those under greater metabolic stress respond well to this nutritional strategy. Supplementary fat sources like vegetable oil and commercial ‘by-pass fat’ supplements are regularly used.

It is important to manage the ratio of saturated versus unsaturated fats being fed in the diet.

How much protein during warmer periods?

In hot conditions cows still need sufficient amounts of protein in their diet to maintain rumen microbial function and supply good flows of amino acids to the intestine. They are faced with three challenges;

- Their daily feed intake is reduced.

- Their rumen microbial function is compromised.

- Summer pastures are lower in protein.

Feed higher-quality protein sources in the diet during the hot season. Higher ‘by-pass’ or ‘escape’ protein sources that are readily digested in the cows’ small intestine can help offset lower yields of microbial protein from the rumen during hot weather.

-

Fibre and starches for heat stress

With daily dry matter intake (DMI) reduced over summer, the quality and amount of fibre and starches can assist heat stress management.

High quality fibre will maintain rumen stability and increase nutrient density without producing excessive metabolic heat. Low-quality forage (high NDF) gives too much dietary bulk and makes it difficult to reach the daily nutrient intakes needed for milk production.

Higher fibre intakes add safety and help cows return to good health after an excessive heat event has passed.

Mixer wagons that allow feeding fibre with other feeds in a partial mixed ration (PMR) give much more flexibility. It is best to feed the PMR under shade between the morning and afternoon milking and allow cows to graze best-quality pastures overnight.

Ensure all cows get equal access when feeding out quantities of forage fibre to your herd. Heifers and less-dominant cows may be more at risk of acidosis than others.Starches as a source of glucose

Heat stressed cows have a greater need for glucose. Provide a form of starch that will slowly ferment so the cow has a steady supply of glucose across the whole body. Corn (maize) is the most readily available slow-fermenting starch source of all the grains.

A slowly fermenting starch source will assist feed digestion in two main ways. Firstly, it takes some of the starch fermentation away from the rumen.

This reduces the rumen energy yield and allows for greater glucose formation in the liver.

It also reduces the risk of ruminal acidosis through excessive starch fermentation. A quickly fermenting starch releases energy too fast and rapid fermentation pushes rumen pH down.

The starch that is not digested in the rumen will normally be digested in the small intestine. At this site of digestion, it produces glucose for use by the gut tissue.

Heat stress affects grain digestion, so manure screening is a good indicator of grain digestion efficiency and informing choices around dietary management.

-

Feed Additives for Heat Stress

Feed additives assist cows in hot conditions in many ways. Some include:

-

rumen modifiers

-

yeast and yeast metabolites

-

betaine

-

niacin.

Rumen modifiers such as monensin, tylosin, virginiamycin, lasalocid and bambermycin may assist by beneficially altering the balance between the different populations of microbes in the rumen and the proportions of volatile fatty acids (VFAs) they produce.

For more information, see the feed.FIBRE.future fact sheet.

Consult your nutrition adviser for more information on what place these or other feed additives may have in your summer nutrition program.

Are buffers necessary?

Cows normally produce more than 2.5 kilograms of bicarbonate-rich saliva every day. Bicarbonates act as an effective buffer against changing stomach acidity and keeps rumen pH within an optimal range. A stable pH range supports the cow’s gut bacteria; an essential component in breaking down the rumen contents.

Hot conditions make cows drool from their mouth instead of letting saliva flow into the rumen. On top of that, heat-stressed cows will have lower concentrations of bicarbonates in their saliva.

A drop in the flow and the bicarbonate concentration means the natural buffering activity is reduced. At the same time, the cow may be consuming less effective fibre and more grain or feed concentrate. This also increases the risk of a fall in rumen pH and ruminal acidosis problems.

Therefore, dietary supplementation with a buffer is good insurance during the hot season. Recommended daily feed rates vary depending on what is fed and how it is fed.Consult your nutrition adviser.

Stock Water & Drinking in the Heat

Ensuring dairy cattle have an adequate supply of drinking water is an important nutrition consideration for dairy farmers. Water is essential for regulation of body temperature, rumen fermentation, flow of feed through the digestive tract, nutrient absorption, metabolism and waste removal.

-