Summer forage crops have the potential to produce high dry matter (DM) yields with a high-water use efficiency (WUE).

However, forage quality can be variable between and within forage type and will be dependent on water and nutrient availability and climatic conditions throughout the season.

This factsheet focuses on C4 summer forage crops that maximise forage production under a late sowing situation.

Plants that use the C4 photosynthetic pathway to grow, are adapted to hotter and drier conditions and are more efficient at converting sunlight, water and nutrients into forage yield. When these plants are provided sufficient water and nutrients for optimum growth, they can produce high DM yields with moderate to high forage quality. Many of the C4 forages used in dairy production systems also produce grain which means they have a relatively high starch concentration but will also be higher in fibre relative to winter (C3) forages.

This factsheet will outline the key management parameters to consider when growing the following summer forage crops post flooding for grazing (forage sorghum and millet) or harvesting for silage (all):

- maize

- grain sorghum

- forage sorghum

- millet

Forage Selection

Selecting summer forages needs to be based on what you want to achieve from the forage (milking cows vs dry stock feeding) and the quantity required. Realistic yields need to be set prior to sowing your forage. Maize hybrids can yield up to 30DMt/ha whereas forage sorghums will yield considerably less but also cost less to produce.

Maize

When selecting maize for silage production, look for hybrids that will suit your region and have a high grain production potential to maximise starch concentration in the silage. If the planting window is narrower, then using a short season hybrid may achieve a higher yield at the same stage of maturity over the same or shorter growing time. Harvest management is critical in producing high quality silage. While delaying harvest may yield extra starch this will lower the silage quality considerably by raising the neutral detergent fibre (NDF). Ideal harvest time is 32–38% whole crop dry matter.

Hybrid Selection

The comparative relative maturity (CRM) value of maize hybrids provides a comparison between different varieties on their time to grain maturity. The CRM may also reflect silage maturity but will be dependent on seasonal conditions at the time. A recent study over two years (2019/20 and 20/21 summers) at Kerang in northern Victoria, compared short and mid-season maize hybrids with a forage sorghum and 2 grain sorghum varieties, found that both maize hybrids reached the target maturity at a similar time with the short season hybrid having a 0.75 to 2.5 tonne higher DM yield compared to the mid-season hybrid. Quality differences between the two were minimal. With a reduced planting and growing window post floods, a short season CRM hybrid may be a better option.

Sorghum

Grain and forage sorghum varieties are hardy, drought tolerant species commonly grown in Queensland and northern New South Wales during the summer period. Forage sorghums and more recently, grain sorghums,are increasingly becoming more widely used as a forage source in temperate and subtropical dairy systems. Risks and growing costs associated with sorghums are reduced when compared to maize crops.

Table 1 Physical characteristics of forage and grain sorghums

Variety selection

Varietal choice will depend upon the desired end point, seasonal and agronomic conditions and flexibility required within the dairy system. Varieties can be grown specifically for grain, silage, grazing and hay, or combinations of these options. Sorghum varieties are commonly hybrids of three parent sorghum types:

Forage sorghums

- Sudan grass (Sudan x Sudan) – display prolific tillering, rapid regrowth, fine stems, open pollination and early flowering, e.g. SSS, Superdan; • Sweet sorghum (female) x Sudan grass (male) hybrids – high dry matter (DM) production, rapid regrowth, drought tolerance and later maturing e.g. Jumbo, Betta Graze;

- Sweet sorghum hybrids – characterised by thicker stems, high sugar levels, slower regrowth, maintain palatability over a longer period and therefore providing potential as a standover feed, e.g. Sugargraze, Mega Sweet, Hunnigreen, Lantern;

- BMR sorghums – bred to express the brown mid-rib (BMR) gene are typically lower in lignin content and therefore higher fibre digestibility, higher metabolisable energy values and similar crude protein to other sorghums. BMR sorghums typically display lower DM yields and can be more prone to lodging, e.g. BMR Rocket and BMR Octane.

- Grain bearing forage sorghum – a high-yielding white grain bearing forage sorghum hybrid that has similar digestibility to maize and the potential to regrow after cutting e.g Graze-N-Sile.

Grain sorghums

- Grain x grain types – They are suitable for silage production as the shorter stature of the plant makes them less prone to lodging when compared to some of the forage sorghum types. They also have a larger seedhead and seed size compared to forage sorghums, therefore the starch levels in the harvested forage will have a higher concentration and availability. Both red and white sorghums display the ability to ratoon and present a second harvest opportunity if agronomic conditions allow.

- White grain sorghum – there is only one white grain sorghum variety (Liberty) available commercially which has been shown to have a higher starch availability than red sorghums and can be used as a silage option. Dairy farmers in northern Victoria have successfully grown Liberty white sorghum with equivalent yields and quality to northern Australia.

- Red grain sorghums – typically grown for grain production but can be used for silage production. Varieties with a higher stature (Sentinel) are preferred for silage production due to their higher DM yields.

Other considerations

Prussic acid (hydrogen cyanide) poisoning can be an issue in sorghum crops. Prussic acid levels are typically higher in sweet sorghum varieties, stressed plants, crops supplied with high nitrogen levels, low soil phosphorus levels, and when crops are vegetative. Prussic acid toxicity issues can be managed by not grazing with hungry stock, especially if the crop is young or showing signs of stress, provision of sulphur blocks to grazing stock, provision of salt licks and grazing swards higher than 80cm. Ensiling affected crops has been reported to decrease prussic acid content. Check their potential prussic acid levels when selecting varieties for grazing. Sudan x Sudan hybrids do not have high levels of prussic acid in comparison to sorghum. Sudan x Sudan hybrids do not have high levels of prussic acid in comparison to sorghum.

Nitrate poisoning can be an issue with crops grown in high nitrogen soils or supplied with large amounts of nitrogen- based fertilisers, crops that have experienced a halt to the growth or stressed crops. While ensiling and haymaking will not reduce the nitrate levels in a plant, farmers can minimise the risk of nitrate poisoning by altering how they cut forages. For example, cloudy days and cutting forages in the morning can contribute to elevated nitrate levels in the plant and thus should be avoided.

Sorghum ergot is more likely to be seen in crops that have experienced cool and wet conditions, hence usually later sown crops. Ergot is known to be toxic to livestock consuming ergot affected grain with levels higher than 0.3% by weight.

Millet

Millet provides limited benefit to Australian dairy production systems due to their lower yields and reduced quality compared to maize and sorghum. If harvested

with a seedhead the starch availability will be minimal due to seed size and the inability to process it adequately at harvest. Typically, the NDF of millet is generally higher and thus more suited to dry cows or young stock rather than lactating cows. However, the window for planting and establishing millet is wider and therefore offers the opportunity to grow a relatively quick bulk of feed that can be utilised for grazing, hay or silage.

Variety selection - days to maturity

Millets that are available in Australia belong to two

main genus, Echinochloa and Panicum. In the Panicum genus, the main millet used in Australia is pearl millet or Pennisetum glaucum which has a long vegetative state. Millets in the Echinochloa genus have generically often been called ‘Japanese millets’ in the past and are quick growing which will suit a shorter planting window. Forage varieties ofthe Echinochloa genus that are available from seed companies in Australia include Shirohie, Siberian, White French and Rebound. Each of the varieties available may have a place in forage production in the dairying regions in Australia, but dairy farmers should be guided by their agronomist and seed companies to select the most appropriate variety for their own situation and environment.

Basic agronomy

Local advice for all forage types should be consulted to identify the optimum agronomic management within your region. Table 1 provides a guide on the ideal soil temperature and planting time to establish each forage type. Planting rates will be dependent on soil moisture and the availability of irrigation. An approximate time to harvest or grazing is provided as a guide and will be dependent on climatic temperatures and moisture availability.

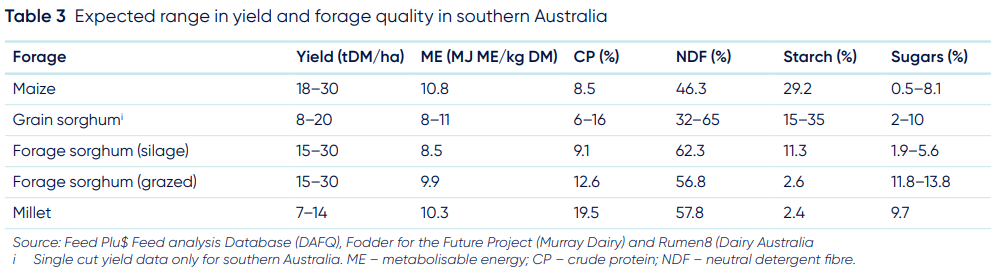

Typical yield and quality of summer forages

Forage yield and quality is highly dependent on stage of maturity, climatic conditions, moisture availability and management, thus the data presented in Table 3 is a guide on the expected yield and quality for southern Australia. Maize will have a higher yield and quality when compared to sorghum and millet. However, this is influenced by

sowing time, as yields declines the later maize is planted, due to a shorter growing window.

When planting later consider:

• Switching to a quicker hybrid as the growing window

is shorter.

• Millets are generally less productive than sorghum.

– In a particularly wet summer, Fisher and Jones (2011)

reported yields of 5.3 to 13.3 t/ha for millets against forage sorghum yields of 21.4 to 30.1 tDM/Ha in crops sown in November at three sites in northern Victoria.

– Dairy Australia, (2018) concluded that for crops grown when they are not unduly limited by water or nutrients, the average yields of millets have been reported to be between 7 and 14 tonne DM/ha whereas forage sorghums yield more at between 17 and 20 tDM/ha.

Grazing management of forage sorghum and millet

Forage sorghum

Forage sorghum has very high growth potential when growing conditions are favourable with high moisture availability and heat. Forage sorghum has been reported to grow 0.5 to 1m in height within a week, therefore managing this forage type in a grazing system can have its challenges. The recommended grazing management guidelines are:

• Graze at 0.5 to 1.2m in height.

• Post-grazing height should be between 15–25cm.

• Mulch every second grazing to reduce stem elongation and an increase in residual height in subsequent grazings.

• If mulching post grazing, cut at 15–20cm in height to reduce tiller deaths and promote tillering.

• To reduce potential prussic acid poisoning issues in animals fed more than 50% of their diet with this forage type, ensure that the crop is at least 50cm in height and not water stressed.

• Drop any grazing paddocks out that have exceeded the ideal grazing height as utilisation will decline rapidly. Harvest for silage or hay instead.

• Drop any grazing paddocks out that have exceeded the ideal grazing height as utilisation will decline rapidly. Harvest for silage or hay instead. The grazing rotation

will be between 2–4 weeks depending on climatic conditions.

Millet

Millet can be grazed between January and March and is often ready for grazing as early as about six weeks after emergence. The following guidelines are recommended:

• The temperate millets may be grazed at a minimum of about 20–30cm in height and up to 50cm.

• The pennisetum varieties (e.g. Peral millet) should be grazed higher at a minimum of about 40–60cm (Callow, 2013).

• Millets do not stand harsh grazing and recovery from grazing is usually slower than that of forage sorghum.

• Millets should not be grazed below about 20cm as damage to the growing point will kill the plant.

• A grazing rotation of 4 to 6 weeks during summer is recommended to prevent the plant from going to head which will reduce feed quality.

Diet considerations when feeding sorghum silages

On paper, maize silage is generally superior across several quality parameters (Table 2) including metabolisable energy (ME), neutral detergent fibre (NDF) concentration and digestibility, lignin and starch. Forage quality can vary considerably within and between forage types due to management, climatic conditions, and variety, so it is extremely important to conduct feed analysis on your forages regularly to understand the amount of variation in forage quality. This will make balancing diets easier and result in better milk responses to nutritional changes.

Balancing the diet

Given the complexity in managing ruminant diets, it is highly recommended that farmers consult a trusted nutritionist to ensure feeding strategies are correct for

the feed source/s being utilised. It is recommended to get a feed test done that gives you starch concentration and starch digestibility. This needs to be done regularly, particularly if silage from different paddocks or growers is being used.The key to balancing the diet with sorghum forages includes:

• Balance for NDF as a percent of the total diet rather than substituting one for one with corn silage.

– The higher NDF concentration in the sorghum will result in lower DM intakes and lower production responses.

• Discount the starch concentration of forage sorghums to 5% as it is likely most of the starch within the grain will pass through the cow and not be available for digestion due to the small grain size and the inability to process is adequately.

• Increase the crude protein (CP) of the total diet to try and utilise the higher fibre within the sorghum forage.

• Feeding higher levels (target 17–18% CP in the total diet) of a good quality protein meal such canola or soybean meal will improve rumen digestion and increase DM intake.

• Cows tend to have higher DM intakes on sorghum-based diets which is possibly due to the chop length of the silage and passage rate through the rumen.

• Given this, it is advisable to offer 5–10% above requirements to ensure DM intake is not being limited in total mixed ration system.